Installation view, purgatory EDIT: The Liberation Archive for the Cyborgs of Now, 2025, transmediale studio x silent green x European Media Art Platform (EMAP), Berlin, DE | image by Laura Fiorio.

The studio visit that follows is a review of Ali Akbar Mehta’s work by researcher, curator, and writer Rachel Be-Yun Wang. Wang explores Mehta’s research during his 2024 residency as well as additional work in discussion with the artist.

The archive is not a static repository of facts, but a contested space – one shaped as much by absence and erasure as by inclusion. Working across digital media, installation, text, and participatory systems, Ali Akbar Mehta’s practice navigates the uneasy, existential terrain of memory and forgetting, rooted in questions of collective memory, violence, and digital publics. Initially trained as a painter and now working with systems – databases, platforms, collaborative archives – Ali engages the archive not just as a document or a static object, but as a state of ongoing process. For Ali, the archive is an active relational technology: something that doesn’t merely store knowledge but organises power. His projects ask what it means to inherit trauma, to witness violence at a remove, and to archive under conditions of collapse.

The work he was developing at Delfina, The Precarious MOB (2023 –) is a ‘technomediated performance of “machine-oriented-bipeds”’. Loosely inspired by Samuel Beckett’s The Lost Ones – a text without dialogue, plot, or resolution – the project transforms Beckett’s world-building narrative into a data-driven, movement-based system. In Beckett’s world, silent characters move in varying levels of despair, within an 18-metre tall cylinder, locked into motion pre-defined by internal social hierarchies. Ali updates this metaphor for a world governed by surveillance capitalism and data-driven behavioural cues. His characters are choreographed not by emotion or intent, but by metrics: stock prices, pollution levels, server pings. An imaginary planetary entity called MOON (Meta Ontology Operational Network), uses this data to design productivity – encouraging the mechanisms of performance that replicate bureaucratic logic, where affect is quantified, and agency is gamed.

The gamified arena echoes the everyday interfaces we already interact with. Ali’s Beckettian sensibility is not speculative fiction – it’s a mirror held up to algorithmic governance, to platform economies, and to the absurdity of constant optimisation and its granularity. With an interest in systems that go nowhere, in structures that persist despite their own futility, the project conjures Beckett’s famous expression at the end of The Unnamable (1953), ‘I can’t go on. I’ll go on.’

Rather than falling into nihilism, this project explores the pervasive vertigo and awe induced by planetary-scale infrastructures, like finance, war, and the technologies that enable them. When the ideologies that underpin these technologies seem so immutable, of mythical providence beyond the scale of the individual, Ali’s practice attempts to take up this proposition and ask of us: how do we de-mythologise our memories, our archives? How do we build systems that hold the scale of planetary violence without aestheticising it?

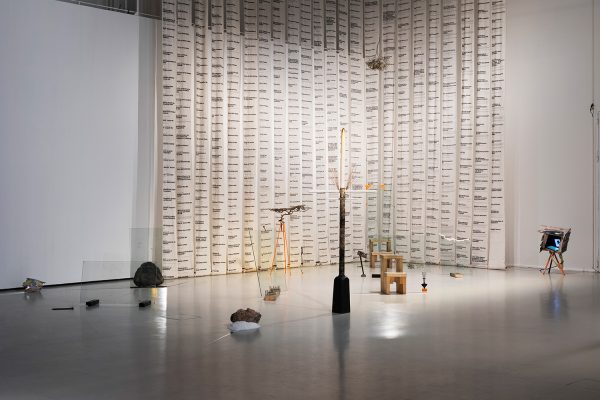

Take purgatory EDIT (2022 – ), a durational, research-based project developed as an archive and participatory installation. At its centre is the Doomscroll Archive, a massive databank of 30,000 video clips (and growing), all manually tagged by Ali himself using a system of emotional intensity categories. Each clip depicts something one would see on social media today – war footage, police brutality, environmental collapse, but also moments of calm, ambiguity, and even beauty.

Here, the concept of ‘data fatigue’ becomes central. Drawing on the aesthetics of Antonin Artaud’s theatre of cruelty and A Clockwork Orange’s infamous negative aversion therapy, Ali renders spectators into test subjects, complicit observers who must confront their own thresholds. What stresses them? What doesn’t? What has already become background noise? In purgatory EDIT’s latest iteration at Transmediale in Berlin, visitors were linked into the video repository through an EEG brainware and a brain-computer interface (BCI) that reads their neural responses, as emotions, to the intensity of the clips. This data is fed back through a custom software that tailors a bespoke sequencing of the clips, turning the act of viewing into a feedback loop. The archive doesn’t simply show violence – it interrogates how we feel it, metabolise it, become numb to it. Viewers are transfixed not by spectacle, but by the dull rhythm of it – the banality of the images, the eerie familiarity. ‘Oh, I could watch this for hours,’ Ali recalls someone saying. The implication is that we already do.

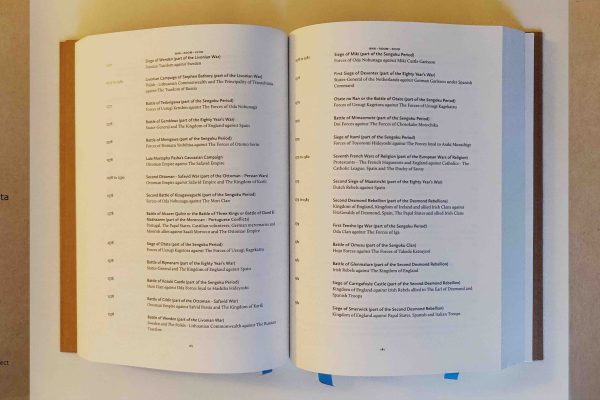

On the conditions of narrative collapse, Shumon Basar has noted that contemporary life no longer unfolds in linear stories but in curated information – beyond the swipes and scrolls of a feed, think lists, indexes, and timelines. Ali’s archives echo this logic. The War List CODEX, a part of his WAR ROOM ECHO (2014 – ) project, for instance, is a 5,525-year-long history of planetary conflict – thousands of wars, rebellions, and uprisings catalogued not just as singular events but as points in a nearly continuous timeline. There are only a handful of years without conflict, and tracking this perennial feature of civilisation has also changed the way this project has developed. With his training as a painter, Ali had originally drafted this as a digital appendix to accompany a figurative mural, but it’s now developed into a life-long work-in-progress, manifesting as part installation, part web interface, and part book. It operates like a columbarium: data as mourning, archive as ghost.

Ali aligns his practice with ‘post-representational ethics’ – making work that is contingent on participation, exchange, and communal authorship. His archives are open-source and decentralized, available for remixing, redistribution, and built for public use. This openness is an ethos as much as it is a technical feature; knowledge is not a fixed object but a civic responsibility. The archive, for Ali, is not only a witness but a testimonial that implicates its users in the act of remembrance.

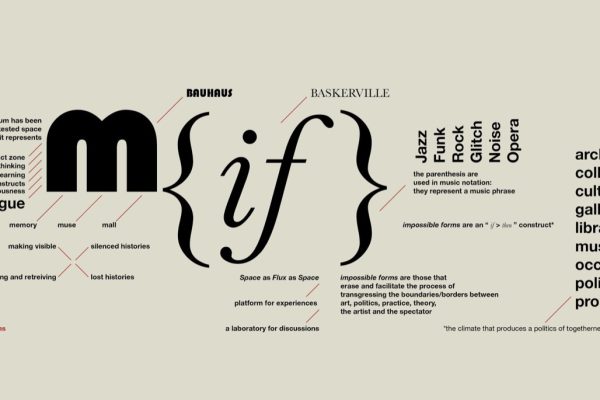

Commitment to counter-hegemonic knowledge systems is crucial to Ali’s practice as a curator and cultural worker. As co-founder of the Museum of Impossible Forms in Helsinki, and its co-artistic director from 2018 to 2020, Ali helped create a space for alternate pedagogies – hosting music workshops, performative archives, and postcolonial methodologies. With the acceleration of education’s corporatisation and the right-wing reshaping of public discourse, his projects ask: what would an ‘internet of awareness’ look like? What are the tools for building a post-colonial, open-source civic archive? And crucially: how do we ensure these tools don’t get absorbed back into the very systems they resist?

With what we all know about the co-optive logics of platforms, about the ways resistance gets aestheticised and monetised, there is no techno-positivist utopia here. Paraphrasing Audre Lorde, Ali asks, ‘how can we use our own tools now that the master has taken them up?’ With awareness of the modernist fallacy of monumental thinking, his projects can become tools for reworking, for resisting erasure, for sitting with the horror without becoming inert.

If contemporary life is defined by being codifiable, searchable, and endlessly scrollable, then Ali’s projects offer a sense of recalibration; not as catharsis nor resolution, but rather a suspension – refusing to resolve the tension of histories, and their systems, that seem too large to hold. What if we spent more time with what we already know? What if we let the data break us open, not shut us down? And what if witnessing could be the beginning of community?

Rachel Be-Yun Wang works in curating and art-making, with a practice that involves exhibition, written, and studio production. Her current interests include methods of exhibition and dissemination, new media art, environmental humanities, and archival narratives. She was the 2023–24 Asymmetry Curatorial Research Fellow at Chisenhale Gallery. In this post, she has worked on the exhibitions, publications, and public programmes of artists Lotus L. Kong, Benoît Piéron, and Alia Farid (all 2023); Joshua Leon, Rory Pilgrim, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, and Bruno Zhu (all 2024); and Claudia Pagès Rabal, Dan Guthrie, and Grant Mooney (all 2025). Previously, she has been involved in exhibition projects such as the Beijing Art and Technology Biennale: Synthetic Ecology (798CUBE, 2022), Ever Archive: The Publications and Publication Projects of Hans Ulrich Obrist (Serralves Foundation, 2022), and Material Tales: The Life of Things (Central Academy of Fine Arts Museum, 2021). Rachel has guest lectured at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in China, produced multiple publications and vitrine exhibitions with the Hans Ulrich Obrist Publication Archive, and pursues an independent writing and artistic practice.